Students Offer Object Analyses from Place, Nations, Generations, Beings

In Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums, Professor Amy Lonetree writes: “Museums have changed significantly from the days when they were considered ‘ivory towers of exclusivity.’ Today, Indigenous peoples are actively involved in making museums more open and community-relevant sites.”

In the past few years, Yale’s Indigenous students, staff, and faculty have organized movements to raise awareness about collecting and exhibition practices related to Indigenous art and artifacts. These efforts culminated in the student-led curation of Place, Nations, Generations, Beings, the Yale University Art Gallery’s first exhibition of Indigenous North American art in its history.

Throughout this exhibition, curators Katie McCleary, Leah Shrestinian, and Joseph Zordan engaged in collaborative processes with museum staff and scholars, Indigenous students, and local Indigenous leaders. Ultimately, Place, Nations, Generations, Beings stands as a testament to an ongoing transformation of museum practice—one that prioritizes collaboration, solidarity, and agency for Indigenous communities. The exhibition also includes a catalog, Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2019), with an introductory essay, co-authored by McCleary and Shrestinian, “Entangled Pasts, Collaborative Futures: Reimagining Indigenous North America Art at Yale.”

During this current semester, students in Professor Ned Blackhawk’s Writing Tribal Histories seminar engaged with scholarship and objects relating to this historic exhibition. In particular, students were invited to offer object analyses drawn from the Place, Nations, Generations, Beingsexhibition and to do so in conversation with McCleary and Shrestinian’s essay.

Although class meetings have been canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many students found ways to reflect on and respond to the exhibition in a digital manner. They drew upon the objects from the exhibition and extended the interpretive analyses provided by the curation staff.

Drawing upon studies of the intersection of Indigenous and museum studies, the below analyses offer explorations into themes of Indigenous resistance, knowledge sharing, and artistic methodology.

Artist:Artist Once Known, Anishinaabe

Piece/Work Title:Birchbark Tray

Date:c.a. 1840

Description:Birchbark and porcupine quills with dye

Size:3 ⅛ x 13 x 5 ⅞ in. (8 x 33 x 15 cm.)

Collection:Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (YPM ANT 0.029084)

The artistic process behind the “Birchbark Tray” depends on intergenerational sharing of cultural memory and practices. Quillwork requires an in-depth understanding of proper harvesting and preservation techniques for birchbark, porcupine quills, and sweetgrass as well as the traditional histories and beliefs that inform the artwork’s design. This art form has historically been an elite one, so the artist likely gained these skills from high-ranking elders and the community’s quillwork society and, later on, educated younger artists in a similar capacity. Thus, the “Birchbark Tray” not only stands as a tangible representation of Ojibwe practices and belief systems, but it also illustrates the ability of quillwork art to foster the distribution of cultural knowledge among Anishinaabeg communities during the 19th century and into today.

One can also understand the “Birchbark Tray” as an attempt to retain Anishinaabe cosmology in the face of forced conversion under the mission system. The tray’s catalogue caption describes the early nineteenth-century mission perspective: “Christian missionaries promoted quillwork among the Anishinaabeg as an example of Indigenous ‘industriousness,’ likening it to European embroidery, which was similarly encouraged for Christian women and girls.” While the missionaries believed that quillwork would assist in their goals to convert the Ojibwe toward Christianity and erase their traditional beliefs, the opposite proved true: within their work, artists embedded spiritual symbols to perpetuate their cosmology. As Shrestinian notes, the X at the center of the tray is reminiscent of the four directions, a foundational principle that relates to Anishinaabe conceptions of the seasons, the stages of life, and the four races of humanity. One can reinterpret the “arched motifs near the handles” as depictions of Animkiig (Thunderbirds), which are arguably the most powerful spiritual beings in Anishinaabe cosmology. Furthermore, when taken together, the two petal-like shapes flanking the center of the X can be seen as a turtle, reinforcing Ojibwe oral histories of Turtle Island and the creation of the world. Through this practice, Anishinaabe artists cleverly and covertly rebelled against their oppressors and adopted mission labor to their advantage, ultimately contributing to the continuation of Indigenous ways of thinking and being.

—Meghanlata Gupta, Yale Class of 2021

Artist: Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band of Cherokee)

Piece/Work Title: Our Lands Are Not Lines on Paper

Date: 2012

Description: Arches watercolor paper splints with archival ink and acrylic

Size/Form: 10 3/16 × 7 1/2 × 6 3/8 in. (35.9 × 19.1 × 16.2 cm)

Collection:Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of the Patti Skigen, ll.b. 1968, Collection, 2019.48.30

Goshorn’s Our Lands Are Note Lines on Paper challenges the removal and abstraction of Indigenous geographies that takes place through the process of settler mapmaking. The process of mapmaking addressed in Goshorn’s work and those of salvage anthropology and artifact and object removal discussed in McCleary and Shrestinian’s introductory article show how the de-contextualization of Indigenous knowledge results in erasure. Goshorn’s piece, in this context, represents a reassertion of Indigenous ways of belonging to land through juxtaposing them over a settler map.

Like in the case of artifact collection, removing and re-ascribing geographic knowledge from Indigenous communities “threatened the existence of…current and future indigenous practices.” Settler-constructed maps were devoid of Indigenous understandings of land; mapmakers, like salvage anthropologists, “approached their studies from settler perspectives….lacked the cultural knowledge to interpret Indigenous materials correctly.” Ultimately, settler understandings of land that were embodied by maps were antithetical to Indigenous beliefs.

The physical locations of objects given to settlers by Indigenous peoples were often co-opted by mapmakers into maps that divided Indigenous land into settler property at the individual and nation-state level. Once land was denoted as property, maps became “means of justifying indigenous peoples exclusion from state societies” and often were crucial in carrying out genocidal policies of land allotment such as the Dawes Act. This “incompatibility between settler notions of land ownership and Indigenous understandings of belonging to a place” is displayed in Goshorn’s work, and Goshorn also challenges settler geographic knowledge as erasure through placing indigenous ways of knowing over a settler map.

Goshorn’s basket superimposes a photograph of the Smoky Mountains with traditional “Mountain/River” design over a settler colonial map of the same area. Goshorn’s photograph of the Smoky Mountains and the weaving design with which it is incorporated into the basket represent the Indigenous practice of using “natural landmarks to establish boundaries,” as opposed to artificial borders imposed by settler nations, challenging maps that depict the opposite. The weaving of the “traditional zigzag design….known as both the ‘Mountain’ and ‘River’ design” over the settler map re-asserts “the Cherokee interpretation of place.” Goshorn demonstrates that in spite of settler colonial processes that erase Indigenous ways of knowing while profiting off of them, such as salvage anthropology and mapmaking, Indigenous knowledge is alive and well.

—Mariko Rooks, Yale Class of 2021

Artist: Peggy Scott Vann / Margaret Ann Crutchfield (Cherokee)

Piece Title: I-hya Talu-tsa (River Cane Basket)

Date: ca. 1810-1815

Description: River cane with walnut dye

Size: 3 15/16 x 8 1/16 x 4 1/16 (10 x 20.5 x 10.5 cm)

Collection: Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, YPM ANT.146788

In the past, scholars have jostled between the terms settler, white, Indigenous, and Native American. To be a settler is to be white, and to be Indigenous is to be Native American. This basket in its very existence works to undermine this dangerous binary in American ethnographic research. Being non-Indigenous does not mean one is a settler, a perpetuator of settler-colonialism. As demonstrated by the Cherokee slave-owner who likely originated this piece, being Indigenous—the original proprietors of the land—does not preclude one from perpetuating settler-colonialism on other displaced Indigenous people.

The I-hya that contributed to the basket was likely harvested by her field slaves, and her house slaves may have contributed cultural and intellectual capital in helping make the basket. I define these ‘re-settled colonial’ practices within the settler-colonial project as those that operate against other Native Americans or other Indigenous peoples, such as displaced African peoples, on the American continent. This is similar to the logic of slavery as a pillar of white supremacy in Andrea’s Smith’s essay “Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy.” In Smith’s framework, “[a]ll non-black peoples are promised that if they conform, they will not be at the bottom of the racial hierarchy.”In other words, this Cherokee woman oppressed other Indigenous peoples to ascend the racial order. The ‘other’ Indigenous people include the very African slaves that Peggy Scott Vann owned.

African Americans descended from slaves—or Generational African Americans—are displaced Indigenous people. They were taken from their ancestral homes and exploited for the settler-colonial project that was the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Blackness was created as a means to destroy our heritage. As activist Briana L. Ureña-Ravelo writes that blackness was “to make us rootless. If a person has no name, no mother, no tongue, no tribe, no land, no people, she can be whatever you tell her to be–chattel, slave, 3/5ths, alligator bait, nothing.” This is not to say that Indigeneity is not contextual; Indigeneity in Australia is used interchangeably with blackness, and the settlers were white in both cases. Native American peoples are owners of this occupied land. However, the settler-colonial state that is the United States differs in that it also participated in the subjugation of peoples native from another continent to occupy the land that white Europeans settled. The displacement of multitude of different ethnic nations complicates the perhaps simple Indigenous / settler binary that so easily applies to Australia.

McCleary and Shreshstinian were correct in asserting that the relationship between the colonial institutions of museums and history of Native Americans needs to be reimagined. Native American peoples, cultures, languages, and art are as beautiful and alive as they are varied. Additionally, the anthropological methods that have been used to research them so far have failed. But in this reimagination of “Indigenous North American Art” at Yale requires a very shift in the meaning of pedagogical terms that we use to deconstruct the past and frame the future.

—EC Mingo, Yale Class of 2022

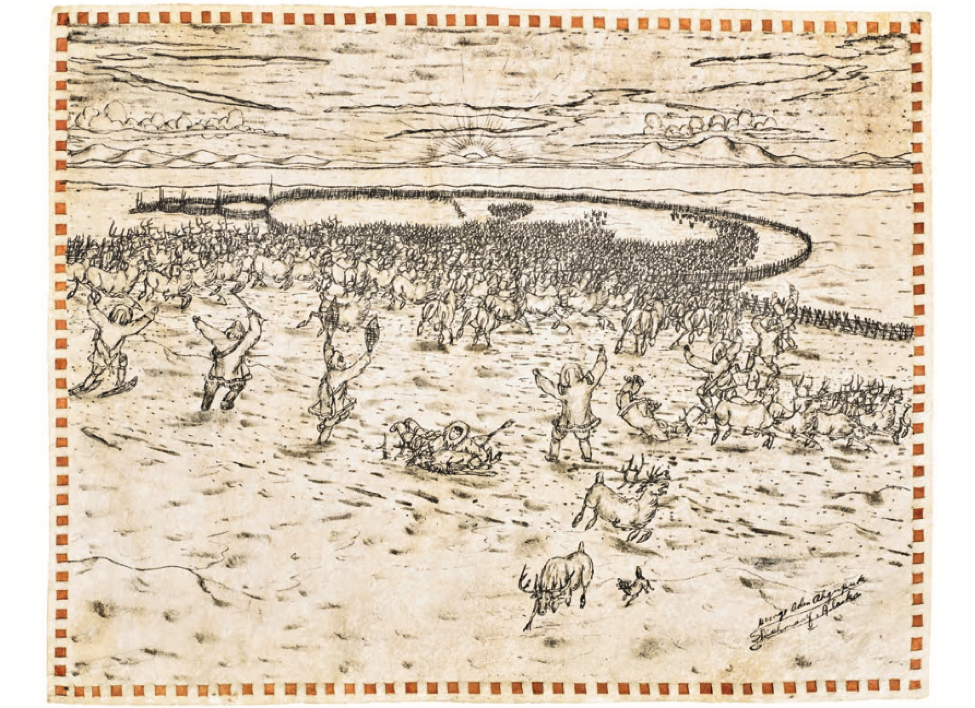

Artist:George Twok Aden Ahgupuk (Inupiaq)

Piece/Work Title: Reindeer Roundup

Date:ca. 1930–39

Description:Ink, reindeer hide, sealskin, and beetroot dye

Size/Form: 12 × 15 in. (30.5 × 38.1 cm)

Collection:Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, YPM ANT.209534

The object in the exhibition under analysis is Reindeer Roundup by George Twok Aden Ahgupuck (Inupiag). The piece is a graphic ink drawing that displays the connection of the Indigenous people to the land in Alaska through the practice of herding and hunting reindeer. The power of the relationship the artist and Indigenous nations have with animals is illustrated through the reindeer. The audience is looking on as a third party observer of a hunting ritual. The vastness of the landscape emphasizes the power of nature, and thereindeer running atthe viewerin the foreground makes the audience feelintimately involved with the piece. This piece ultimately draws an audience in and puts them into thelandscape. The sun peaking out over the distant mountains represents hope: potentially hope for a better tomorrow. This piece has a voice, it tells the story of an Alaskan community adapting to a new lifestyle in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Ahgupuk’s Reindeer Roundup hits the four pillarsof the exhibit—Place, Nations, Generations, Beings—on the head. These themes shinefrom the canvas.

The relationship between the Alaskan Indigenous and the land is entangled. The reindeer is an object of Indigenous societal change. The traditions of reindeer herding and hunting will be passed down. Lastly, the relationship between the artist and the artwork is powerful. Ahgupuk was a leader of a “generation of artists,” his work speaks to not just Indigenous communities then but Indigenous communities everywhere. Settler influence can have a lasting negative impact on Indigenous communities. Ahgupuk’s piece displays asense of positivity and resiliency among Indigenous communities. We see successful reindeer herding and hunting practices.

This idea speaks to the conversation Katie McCleary and Leah Shrestinian proposed—that art galleries exhibiting Native American work must be created with direct help from the Indigenous communities themselves, allowing them to tell their own story. Similar to Ahgupuk’s message, positive outcomes are possible between Indigenous people and non-Indigenous communities when opportunity for Indigenous sovereignty is given. That opportunity is what we must continue to fight for today, and what YUAG’s exhibition represents.

—Phil Kemp, Yale Class of 2021

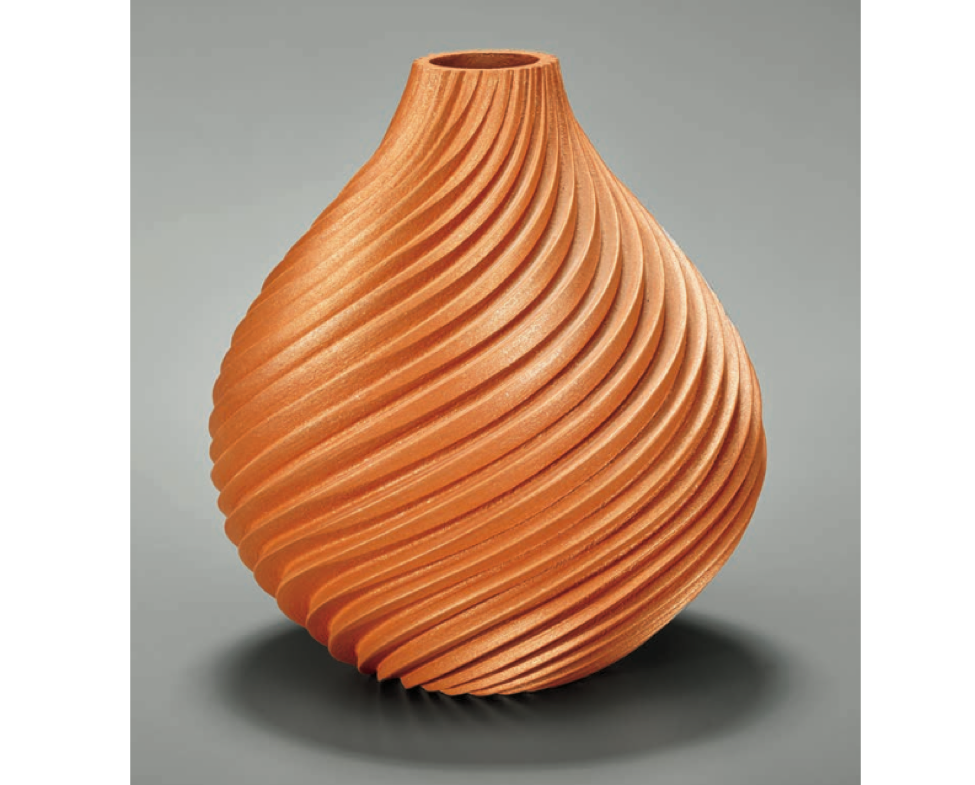

Artist: Dominique Toya / Merriam Camille Toya (Jemez Pueblo)

Piece/Work Title: Jar

Date: 2006

Description: Earthenware, ceramic, containers

Size/Form: 7 ¾ x 7 ¾ in. (19.7 cm x 19.7 cm)

Collection: Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Patti Skigen, LL.B., 1968

According to the YUAG catalogue description, this small red clay jar was purchased from Toya in 2006 at the Santa Fe Indian Market. This art market, originally established in 1922 as a part of the extended Fiesta de Santa Fe (a celebration to commemorate the 1692 Spaniard reconquest of New Mexico), was the work of Kenneth Milton Chapman. Chapman, a well known white artist and archaeologist, began the “Indian Market” as a means to lead the “revitalization” of Pueblo pottery-making. Now, the market has grown as one of the largest Native American art showcases in the world, organized annually by the Southwestern Association of Indian Arts. Historically, the impacts of the Early Spanish settlements and the forced implementation of the Encomienda System contributed greatly to many Pueblo communities falling into poverty. As a result, many Pueblo families developed a reliance on the exchange and/or purchase of their pottery and other objects, which will be discussed in further detail later on.

In relation to Katie McCleary and Leah Shrestinian’s introductory essay within the Place, Nations, Generations, and Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art catalogue, cultural objects such as Pueblo pottery do “…speak to the entangled, often violent, yet ever-changing relationship between their current steward(s)…and the Indigenous nations to which they belong.” In this case, the work of art was purchased directly from the artist and after some time donated to the collection by an individual. Unfortunately, this method of collecting Indigenous items has not been the only acquire such objects, as some cultural artifacts that sit in museums originated from the robbery of burial sites, ancestral homelands, and anything in between. Often these objects were taken without consultation with the tribe or tribes that they belonged to, with many of these pieces and human remains never returned to their families or tribes to this day. In the context of Southwestern pottery, tourism allowed outsiders of Pueblo communities access to many cultural and ancestral sites, including Santa Clara Pueblo’s Puye Cliff Dwellings, Bandelier National Monument, Chaco National Historical Park, and others. Over the years, an increase in outsider presence within Indigenous reservations led to an increase in stolen pottery from ceremonial spaces, ancestral homes within cliff dwellings, and even from the heart of many pueblos villages where dances and annual feast days commence and employ pottery as a part of traditional practice.

The acquisition and purchase of Indigenous objects were often connected to assimilative, capitalist practices forced onto Native communities. The Place, Nations, Generations, Beingscurators state: “Forced to join the settler capitalist economy, [Indigenous communities] sold items they would not otherwise have sold or began making art for the tourist market to survive. Thus, while not technically ‘stolen,’ many of these objects were made and/or parted with under the extreme duress of cultural genocide.” This settler-capitalist economy is what allows tourist markets like the Santa Fe Indian market to thrive and continue on. On one hand, Pueblo communities need the sale of their pottery in order to maintain financial stability, making and selling objects that historically were only intended to be used in the traditional contexts between tribal nations. On the other, tourists gather from all areas of the world to see this collection of Indigenous art, purchasing pottery and other objects as a way of doing one’s part in “preserving Indigenous cultures,” otherwise known as salvage anthropology.

—Aaron Warren, Yale Class of 2023

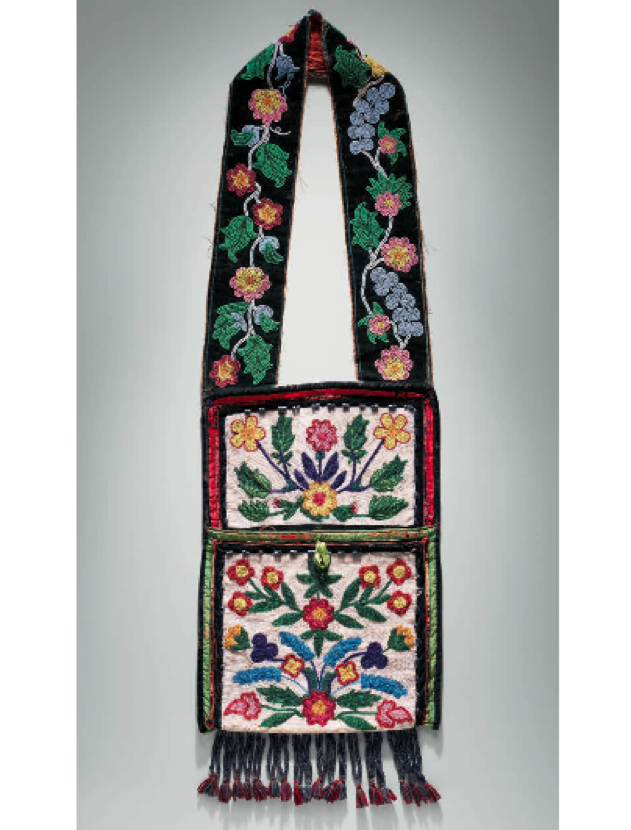

Artist: Once Known

Piece/Work Title: Aazhooningwa’on (Bandolier Bag)

Date: 1890–1910

Description: Glass beads, cotton and silk

Size/Form: 37 13/16 x 12 13/16 x 13/16 in (96 × 31 × 2 cm)

Collection: Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, Department of Anthropology

Aazhooningwa’on is a work dated from 1890 to 1910 that reflects traditional Anishinaabe beliefs on the connections between their peoples and the flora of the Great Lakes woodlands. This beaded shoulder bag is a part of the “Place” section of the thematically organized Place, Nations, Generations, Beings exhibition. This theme emphasizes “the connections that Indigenous peoples have to their lands,” and seeks to display objects which “speak to not only the violence of settler colonialism but also the resistance and creativity of their artists” (6, 54). The exhibition identifies the cultural origin of Aazhooningwa’on as Ojibwe, an Anishinaabe people who inhabit the land around Lake Superior. During the time period in which this object was created, the Ojibwe struggled with the challenges of land loss, economic exploitation and forced assimilation. Decades before their treaty rights struggle, scattered Ojibwe communities maintained their culture amidst immense outside pressure to incorporate into wider American society through practices such as the creation of beadwork art. Aazhooningwa’on is an example of how North American Indigenous peoples tied themselves to their traditional lands despite their dispossession, and its current venue in the Place, Nations, Generations, Beings exhibition chips away at the false dichotomy of “art” and “artifact” previously heightened by the decentralized nature of Yale’s indigenous collections.

The catalog description of Aazhooningwa’on details how the designs of beaded shoulder bags such as this one held ceremonial and spiritual meaning specific to the individual for whom they were made. The flora patterns on this bag likely reflect the unique connection between the wearer and nature. This object displays traditional spiritual beliefs and gathering practices despite being created by an Ojibwe beadwork artist during a time period in which the federal government sought to remake indigenous peoples into Christian farmers through forced allotment and boarding schools. The curators of the Place, Nations, Generations, Beings exhibition planned for the “Place” section to show the enduring connections of indigenous peoples to their territories in the face of settler colonialism, and Aazhooningwa’on reflects this intention by displaying the endurance of traditional beliefs amongst the Ojibwe despite the loss of legal title to the vast majority of their territory.

In their introductory catalog essay, Katie McCleary and Leah Shrestinian discuss how Yale’s indigenous collections are scattered across several institutions as a result of being obtained over time by a variety of scholars and collectors rather than through a consistent, university-wide effort. Consequently, Indigenous works on campus can be deceptively classified. Aazhooningwa’on highlights this problem and demonstrates how the Place, Nations, Generations, Beings exhibition works to resolve this issue. Prior to its current venue, this object was held by the Department of Anthropology of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

This beaded shoulder bag is a beautiful work of art created by an ancestor of current Ojibwe peoples. By housing this object within a natural history museum, however, it is framed as an artifact and considered solely in terms of its scholarly value. Through exhibitions such as the Place, Nations, Generations, Beings, this false dichotomy between “art” and “artifact” described by McCleary and Shrestinian can be broken down in favor of a more representative narrative that acknowledges current indigenous voices.

—John Crawford, Yale Class of 2022

Artist:Artist Once Known; Diné (Navajo)

Piece:Hanoolchaadi(Second Phase Chief Blanket)

Date:ca. Mid- to Late 19th century

Description:Wool with pigment

Size/Form:62 1/2 × 75 in. (158.8 × 190.5 cm)

Collection:Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

Pieces in Place, Nations, Generations, Beings remain entangled among their presence at Yale, in museum collections, their creators, and the tribal nations they once inhabited. As Katie McCleary and Leah Shrestinian note, mechanisms of containment that “made Indigenous nations… more accessible to settler scholars and collectors” aided the creation of museum collections across the continent, including Yale’s. In response, the YUAG exhibit aims to reimagine Indigenous pieces through collaboration and Indigenous-led curation. Such methodologies are centered on four different themes (Place, Nations, Generations, and Beings) dozens of pieces, including a Diné Hanoolchaadi. By exhibiting the blanket and providing specific context, the curators highlight the Hanoolchaadi’s history and transform the blanket from a static artifact usually intended for the settler gaze to a portrait of survivance and sovereignty.

The curators of Place, Nations, Generations, Beings date the Hanoolchaadi during the mid- to late nineteenth century, a time of “intense dispossession and displacement of many Indigenous nations.” Although a specific set of dates are not specified, the estimate falls around the dates of the Long Walk of the Navajo (1863 to 1866), during which Kit Carson’s troops forced the Diné on a death march to Bosque Redondo, New Mexico from their original homelands in and around so-called Arizona. The acquisition of the Hanoolchaadi, then, falls around a period of Diné cultural genocide, imprisonment, and deportation. Although Diné traded Hanoolchaadi, as the YUAG catalog notes, before “settlers became interested in acquiring them,” additional contextualization begs the question of the circumstance under which the blanket was acquired. Many Hanoolchaadi were used for trading among settlers, who sought the blankets for their complex designs and high quality, but given the estimated dates, one must decenter the blanket from settler trade settings and consider increased pressures on Diné peoples and weavers to barter important pieces for protection, restricted goods, and homesteads. The piece ties, then, directly into Cleary and Shrestinian’s note that “even legal purchase and acquisition… were very often tied to violent assimilationist practices” (22), and the Hanoolchaadi was likely parted with under “the extreme duress of cultural genocide” (22). Repositioning the blanket in an Indigenous-curated museum setting rather than a private collection, trading post, or historical exhibit allows for reflection on the nature of the blanket’s acquisition and its own history, rather than a superficial settler valuation of aesthetic and rarity.

The catalog additionally places the Hanoolchaadi in the “Nations” theme of the exhibit, which largely emphasizes the self-representation at the core of Indigenous sovereignty. Alongside other pieces that survived imprisonment and assimilatory efforts, theHanoolchaadi also represents artistic exchange as a result of relocation in the mid- to late nineteenth century, and a preservation of traditional knowledge despite ongoing cultural genocide. Weaving, an integral part of Diné culture and matriarchy, is a talent chosen from a young age by specific Diné women who then practice their craft for life. The creation of blankets like Hanoolchaadi represent an assertion of sovereignty through self-representation and preservation of cultural practices, despite necessary adaptations to settler economies and desperate measures to secure resources and safety during periods of removal. Though, as the catalog notes, Diné used “Chief blankets” to engage with settler traders, such pieces have played a vital role in preserving traditions of Diné self-representation. The curators’ “Nations” theme transforms the blanket, then, from a static artifact and familiar “trading post” staple meant to be observed and collected largely by settlers to an enduring portrait of Diné survivance, sovereignty, and matriarchy. By purposefully working against chronological and ethnographic models of organization that align with settler understandings of time and importance noted by McCleary and Shrestinian, the curators reject settler colonial categorization and representation.

—Kinsale Hueston, Yale Class of 2022

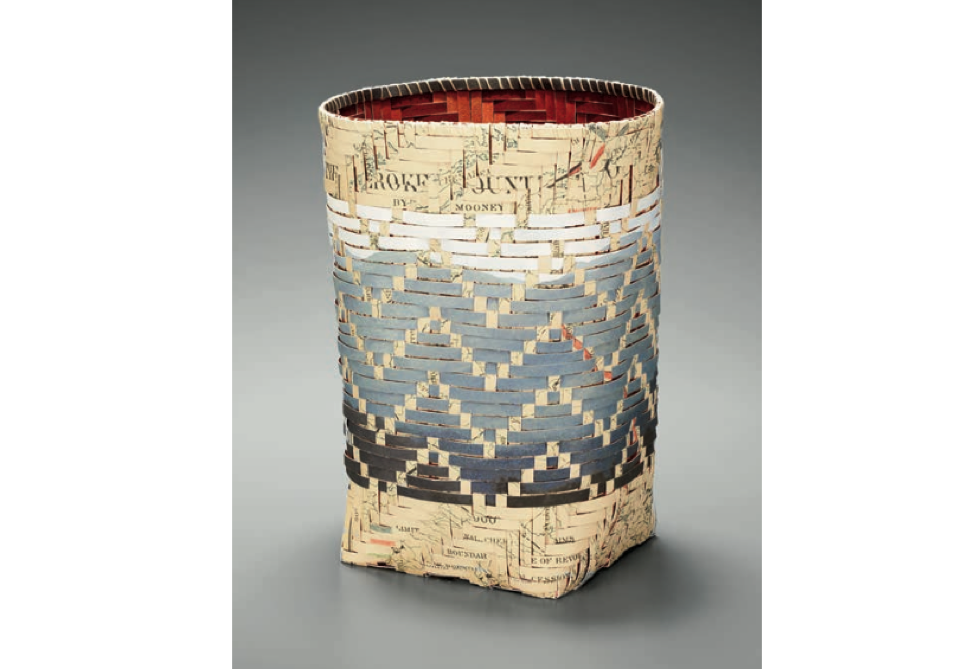

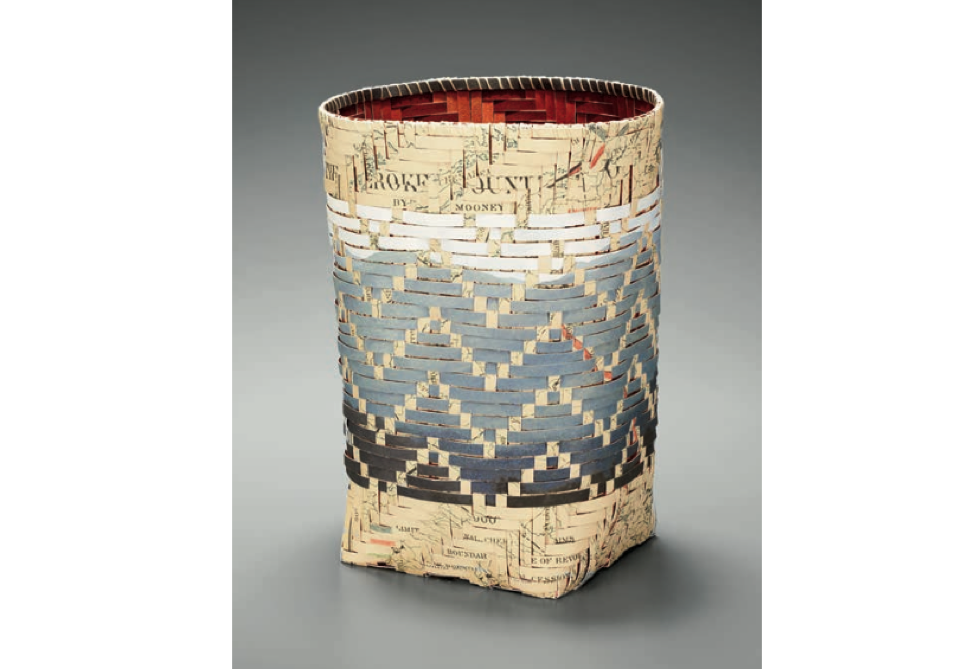

Artist:Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band of Cherokee)

Piece/Work Title:Our Lands Are Not Lines on Paper

Date:2012

Description:Arches watercolor paper splints with archival ink and acrylic

Size/Form:10 3/16 × 7 1/2 × 6 3/8 in. (35.9 × 19.1 × 16.2 cm)

Collection:Yale University Art Gallery, Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund, 2018

Shan Goshorn’s Our Lands Are Not Lines on Paper works to combat the reductive rendering of land as maps and to disrupt settler forms of logic in favor of reasserting Cherokee knowledge. Goshorn accomplishes this by deconstructing a settler map of Cherokee territory. This basket makes the argument that the imposition of maps onto land transforms the land into an object of study, suggesting that the relationship between people and land is static and ahistorical rather than dynamic and reciprocal. The settler understanding of land as object parallels Katherine McCleary and Leah Shrestinian’s discussion of the work of anthropologists in regarding Indigenous art as “natural history” and “objects of study.”

Through Goshorn, McCleary, and Shrestinian’s understandings, the act of mapping is the act of constructing a discourse and ideology not only about the land, but about Indigenous forms of knowledge as well. Goshorn affirms the Cherokee understanding of the people-land relationship over the settler understanding of this relationship as person-object or owner-property.

Shrestinian writes that the Cherokee interpretation of place through natural landmarks is represented both in the zigzag mountain or river pattern and in the basket’s natural materials. These materials come from the land; their use itself reflects the importance of the people-land relationship for Goshorn. The use of these materials in art reveals that Cherokee cultural production and identity cannot exist separately from their relationship to place. The combination of the photograph of the Great Smoky Mountains and the historical map of Cherokee territory shows two competing logics. Goshorn weaves these two images in different directions; each one obstructs the other, suggesting that they are incompatible. These two images, then, reflect two ways of understanding land. Cherokee knowledge is at the center, with the image of the mountains whole and recognizable, while Goshorn places the map at the margins and shreds it to obscure its meaning. The color photo gives a more accurate visual representation of the land, while the map flattens the land and forces paper and ink to accommodate it; Goshorn reveals how the map’s framework fails.

Goshorn disrupts the idea of the map as objective, revealing its constructed nature, and the constructed nature of the ideology it represents, through deconstruction and reorientation. Goshorn breaks the map into its parts and rearranges them in her weaving, making the map illegible, and in doing so she reveals the unintelligibility and artificiality of maps themselves. The word “boundary” is partially visible, pointing to Goshorn’s disruption of settler boundaries. The curators of the exhibition take up the systemic fragmentation of indigenous systems of order as it exists at Yale, with Indigenous objects existing in “disparate collections across campus” by bringing them together and organizing them thematically. Goshorn takes up the same project by fragmenting a settler map, cutting it into strips to be incorporated into a Cherokee artwork of resistance and reclamation. This disruption is an inversion of settlers’ discursive violence in rejecting indigenous conceptions of land. Importantly, Goshorn does not cast away the settler map in favor of a basket that uses only traditional Cherokee images or patterns. Rather, Goshorn incorporates settler logic to acknowledge its place in Cherokee history, expose its faults, and use it in her project of imagining indigenous and Cherokee futurity. In this way, the map is repurposed for an act of indigenous resistance.

—Katherine Salinas, Yale Class of 2021

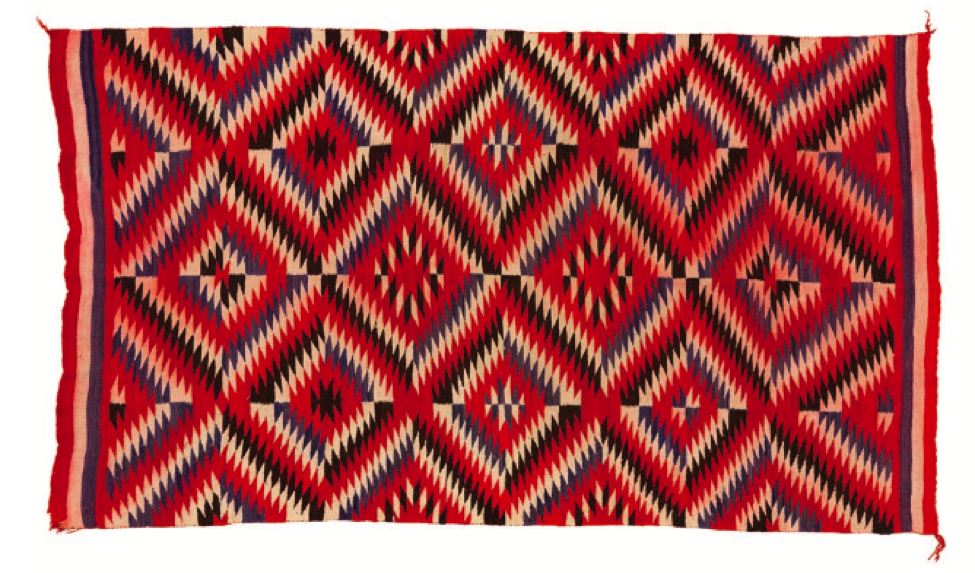

Artist:Artist Once Known; Diné (Navajo)

Piece:Eye-Dazzler Blanket

Date:ca. Late 19th century

Description:Wool with pigment

Size/Form:53 x 96 in. (134.6 × 243.8 cm)

Collection:Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

Across North America, museums continue to misrepresent Indigenous art and reinforce colonial ideas by portraying Indigenous history as static and dependent on settler arrival, which perpetuate primitive stereotypes. As Dr. Amy Lonetree notes, “Museums can be very painful sites for Native peoples, as they are intimately tied to the colonization process.” Yale scholars and anthropologists have exploited Indigenous communities and stolen art and artifacts for academic purposes, which remain in the museums today. Removing Indigenous belongings has aided the genocide of Native peoples, as it allowed for the nation-state to assimilate them into the settler colonial society. These efforts of assimilation and erasure led to misrepresentations in Yale’s museums, which McCleary, Shrestinian and other Indigenous communities are trying to accurately reinterpret in these inherently settler-colonial spaces. Within the exhibition of Place, Nations, Generations, Beings, the curators provide a description for a Diné blanket, entitled Eye-Dazzler Blanket, that prioritizes the Diné voice and rejects the typical geographic and ethnographic museum placement of similar Indigenous pieces.

In the exhibition, the catalog description itself explicitly prioritizes the Indigenous voice by starting off the description with stories from Diné oral history about Spider Woman. The description also notes that in Diné culture today, women who have chosen weaving as their skill then teach their daughters, making this practice of great social and economic importance. The inclusion of Diné oral history, recognition of important cultural aspects such as Spider Woman, and emphasis on cultural relevance all resemble McCleary’s and Shrestinian’s objectives in future museum and Indigenous collaborations.

To achieve these objectives of Native collaboration, accurate representation, and more, McCleary and Shrestinian organized the museum thematically, rather than chronologically or ethnographically, which many settler museums still do today. They argued that a chronological order of Indigenous history and art are in line with the settler understanding of time, as some Indigenous nations view time as a unity and that the past, present, and future overlap and influence each other. Ethnographic organization also proved to be problematic, as it implied that Indigenous nations were independent of one another and indirectly portrayed that nations placed at the front of the exhibit were more significant. In the Eye-Dazzler Blanket, the catalog description proves that the ethnographic order would erase the relation the Diné nation had with various Hispanic communities and weavers in the Southwest. The Saltillo Serape was an integral part of horse culture and fashion in the early 19th century, and interactions with these

communities gave rise to this pattern in Diné art. A settler-colonial exhibition organization ignores these interactions and the influence of culture between nations, while the exhibition’s aim emphasizes the cross-boundary flow of cultural ideas and practices that populated the Diné’s ancestral homelands.

Comparing the Eye-Dazzler Blanket with the introductory catalog essay, McCleary and Shrestinian achieve their objectives of prioritizing Indigenous voices and rejecting the organizational methods of settler colonialism. Presenting the blanket as an object of study would be based on settler understandings of Indigenous history, but McCleary and Shrestinian emphasize that one should see that Indigenous art and artifacts are “beings, ancestors, and relations, as well as objects to be both cared for and used.” The blanket embodies the ideas of McCleary and Shrenstinian, rejects these settler understandings of history, and encourages further Indigenous collaboration and accurate representation of contemporary Indigenous art.

—Clayton Land, Class of 2022

Artist: Artist Once Known (Lakota)

Piece/Work Title: Dress

Date: Late 19th Century

Description: Hide (possibly elk) with glass beads

Size/Form: 61 x 481⁄2 in. (154.9 x 123.2 cm)

Collection: Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

Considering the importance of decolonization through presentation, the Lakota hide dress with glass beads defines itself as being – living, breathing, and sentient. Bringing life and story to Native objects – though “object” itself is too static – speaks to the achievement of Yale’s student activists Katie McCleary and Leah Shrestinian, who helped curate the Yale University Art Gallery exhibition “Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art.”

The presentation of the dress is enhanced by its accompanying descriptive plaque and the physical space the dress assumes in the gallery. Within the written description is a quote from Georgianna Old Elk, who owns a similar dress she still wears. Old Elk remarks on the sentimental value of the dress: “When I dance I am never alone. Not only with my dress, but every bit of me or every part was made by family…. I believe in the power of my dress and who made it for me.” Though the majority of the pieces in the gallery do not present associated quotes, displaying Old Elk’s statement strengthens the dress’s declaration as a living being, as it demonstrates a tangible corroboration of McCleary and Shrestinian’s proclamation that “these objects are never silent.” Yet the quote’s content, too, drives viewers to this conclusion. Old Elk’s personalization of the dress, as it reminds her of her own family, brings it to life – contemporary life. Directing viewers to consider those who made the dress – and thus, who are still within it – gives the dress a life that narrates itself.

Allowing “objects” to tell their stories is essential to combatting what McCleary and Shrestinian describe as “the ‘othering’ practices of twentieth century anthropology, which prioritized settler views and often flattened the experiences of Indigenous peoples.” In the context of a Native dress, there is potential for both metaphorical and literal flattening that are intricately tied.

Looking up from the plaque, the dress life’s narration continues to manifest through its physical shape. The curators could have pressed the dress flat within a glass frame on the gallery wall, yet instead it levitates above a stand, with outstretched arms, space to walk around and view it from all angles, and space within it, representing the body that wore it. The arrangement of the dress allows it to be understood in real time – or close to real time – and extends the opportunity for viewers to consider who the dress belongs to and its personal history.

Both Old Elk’s statement and the shape of the dress confront museum visitors with questions McCleary and Shrestinian raise: “Who brought [the artworks] here and why? What have their lives looked like since they arrived, and what did they look like before?” Inviting these questions brings visitors closer to decolonizing individual Native pieces in museums – understanding them as beings with unique histories and personal meanings – and thus, giving them the respect they deserve.

—Stella Fitzgerald, Yale Class of 2022

Artist:Artist Once Known (Tlingit)

Piece Title:Moccasins

Date:ca. 1930-40

Description:Hide (possibly moose), fur, flannel, and glass beads

Size/Form:Each 3 9/16 x 9 7/16 x 3 ⅛ in. (9 x 24 x 8 cm)

Collection:Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

The biggest display case in Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of North American Indigenous Art at the Yale University Art Gallery is devoted entirely to art intended for the tourist market. The case includes a miniature canoe and a miniature totem pole, but perhaps most captivatingly, a pair of moccasins beaded with a floral design and the word “Alaska” on them. Viewers may have an impulse to relegate these tourist objects, as “Indian kitsch” and therefore, “lower” class art; I argue, however, that by using the Alaska moccasins as a case study, that Indigenous art possesses many layers of meaning that defy easy representation, and that it is up to the curators to decide what classifies as “high” or “low” class art.

Each object in this exhibition relates to one of the four themes in the title, and the curators placed the Alaska moccasins in the “Generations” theme for several reasons. As mentioned by the curators in the exhibition catalog, Indigenous art serves as a means for Indigenous artists to pass down cultural knowledge in and around their tribal communities.The Tlingit artist who crafted the Alaska moccasins employs traditional beadwork and materials resembling moose hide to potentially inform buyers of the links between the state of Alaska and Indigeneity. Alaska is derived from the Unangax word “Alaxsxaq” meaning “Where the Waves Break Their Back,” so the artist could be activating buyers’ imaginations of Alaska within an Indigenous context. Alternatively, the curators could have placed the Alaska moccasins in Generations in order to present the need for Indigenous artists to participate in the capitalist market. Indigenous peoples responded to settler structures of financial power by producing work for sale in the tourist economy in order to survive. Therefore, the Alaska moccasins confront viewers to think about the conditions settler colonialism imposed on Indigenous peoples that provided an environment for those moccasins to emerge out of in the first place.

For the curators, the objects in their exhibit are not only there for aesthetic purposes, but a part of a larger project Ho-Chunk scholar Amy Lonetree defines as “truth telling.” Museums must recognize the painful aspects of settler colonialism in what is now the United States for their representations of Indigenous work to be fair. The curators use the tourist display case in their exhibit to effectively reframe the Alaska moccasins as “art” instead of what the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History might present as “artifact.” Within the context of an art exhibit, the moccasins are elevated on a stand with a light shining down on them to indicate to viewers they should be considered for their aesthetic value like the complexity of the beadwork alongside their market value. While the artist of the moccasins is unknown, the curators prompt viewers to think about the individual behind the work along with other unknown artists in the exhibit as “Artists Once Known.” This language is important because it represents that while Yale’s institutions did not locate the artist’s name, the artist–in this case a Tlingit–was certainly known to their home community that this work emerged from. As a result, the Alaska moccasins exemplify the value of tourist art in Indigenous economies and that Indigenous art is more than just artifact.

—Anna Smist, Yale Class of 2021

Artist:Artist Once Known; Diné (Navajo)

Piece:Hanoolchaadi(Second Phase Chief Blanket)

Date:ca. Mid- to Late 19th century

Description:Wool with pigment

Size/Form:62 1/2 × 75 in. (158.8 × 190.5 cm)

Collection:Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

The Places, Nations, Generations, Beingsexhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery features a remarkable amount of Indigenous art within an institution that has consistently relegated indigenous works to the category of “natural history.” This new display allows for an approach to Indigenous pieces that acknowledges the humanity of those who created these works—both named artists and “artists once known.” This hanoolchaadiexemplifies this methodology, for its presentation within the museum highlights its cultural significance, recognizes its artistry, and emphasizes the importance of continued Indigenous life.

The hanoolchaadi is a large blanket made of dyed wool, with striped patterns of tan, brown, blue, and red. Described as prestige items, Indigenous women would weave these blankets of this kind and trade them between nations before settlers arrived.These settlers renamed the hanoolchaadi“chief blankets,” coveting and collecting them for their attractive patterns and craftsmanship. The Peabody Museum of Natural History held this particular hanoolchaadibefore the curators of this exhibit chose to display it.

While the hanoolchaadiis photographed as a single bolt of rectangular woolen cloth in the art gallery catalogue, the blanket appears within the exhibition as it would be worn by a member of a Diné tribe—draped around a physical form representing the body. In portraying the blanket in this style, a viewer can admire its beauty and simultaneously see the original practical use of such a piece of Indigenous dress. As explained by the curators of this exhibit, “presenting [these] items against white walls as purely aesthetic objects” can drastically “divorce objects from their original contexts.”Though the hanoolchaadi is attractive to look at horizontally, it does not represent the same embodied story as it does when placed upon a figure. This blanket was once worn by an indigenous individual within a community; the ingrained memory of this blanket is intensified by its presentation upon a body. While the artist is “once known” and is not identifiable by Yale’s museums today, the history of the hanoolchaadiremains central to its appearance within the exhibit.

The three-dimensional physicality of this blanket signifies even further—it reclaims the Native body within a university whose museums constantly “reinforce primitivizing stereotypes of Indigenous peoples and promote the misconception that Indigenous peoples no longer exist.” Here, visitors to the art gallery can view the form of a Diné individual without a stereotyped wax figurine. The minimalist mannequin beneath the hanoolchaadigives the piece reverence, demonstrating its grandness, as its sheer size almost consumes the form beneath it. The blanket holds life in this configuration, proving the importance of including Native beings and narratives in a contemporary artistic environment. One cannot deny the personhood within this piece, the embodied history central to its display. Its inclusion within the exhibition brings the continued story of indigenous life to the fore, challenging each viewer to see both the history and future of Indigeneity within the museum.

—Noah Parnes, Yale Class of 2021

Artist: Once Known (Nation Unknown)

Piece/Work Title: Moccasins

Date: ca. Late 19th century

Description: Hide (possibly deer) and glass beads

Size/Form: Each 4 3/4 × 10 1/4 × 3 1/8 in. (12 × 26 × 8 cm)

Collection: Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

Indigenous museum objects not only convey a message due to their presence within the museum (a colonial institution), but also through the ways they’re displayed and described. For instance, as McCleary and Shrestinian point out in their introductory essay “Entangled Pasts, Collaborative Futures: Reimagining Indigenous North American Art at Yale,” the deliberate choice to spatially position Native artifacts following the Great Hall of Dinosaurs or Hall of Mammalian Evolution consigns Native people to the past.

McCleary and Shrestinian begin their essay by condemning practices of constraining objects to “glass cases … wooden drawers and steel cabinets;” nevertheless, that is precisely how these moccasins are displayed. This choice proves perplexing, especially when compared to the intentional display of the Marie Watt piece. Perhaps this display aimed to accomplish their goal of examining “the University’s role in American settler colonialism” by placing the moccasins in the typical glass case, thus pointing out viewers’ voyeuristic behavior. However, the display seems more a consequence of the larger museum institution than a deliberate choice, especially when contrasted with the story told by the presentation of the First Teachers pieces.

The thematic organization of the moccasins within the “Generations” category also proves complicated. The catalog description focuses on the removal of numerous “Indigenous nations from their territories near the Great Lakes to reservations in Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma;” however, this description seems more an effect of their categorization than a cause. McCleary and Shrestinian’s essay clearly justifies the motivation behind the four categories, but what is the purpose behind segregating objects? How is it that these moccasins do not also relate inherently to places, generations, and beings? More specifically, as the authors note, “removing objects from their communities … threatened the existence of not only current but also future Indigenous artistic practices.” This description certainly seems applicable to the moccasins on display. Perhaps the organization would appear more reasonable if the moccasins displayed in other categories (in fact moccasins are featured in every category) included descriptions covering each theme, thus creating a full—albeit segmented—narrative; however, this is one of the only pair of moccasins in the catalogue accompanied by a description. (A pair of moccasins in “place” also includes a description). Ultimately, it seems the moccasins are prevented from conveying their complete significance.

McCleary and Shrestinian prove aware of the issues inherent in presenting Indigenous objects as simply “art” or “artifact” depending on the institution which holds them—an understanding that only partially translates to the moccasin’s presentation. While the description clearly acknowledges the moccasin’s aesthetic value, in avoiding the pitfall of regarding them “simply as objects of study” it neglects to include any technical information whatsoever. Perhaps focusing on methods of production could balance the two, recognizing artistry at the same time as anthropology. Ultimately, these moccasins represent stories largely untold at Yale and similar institutions until recently. The diligent research, organization, and cooperation executed by students and staff remain impressive. However, this exhibition should continue to grow and change as new students and generations of students continually improve upon it.

—Gracie Englebert, Yale Class of 2022

Artist: Artist Once Known; Mohegan

Pieces/Work Title: Basket

Date: ca. 1860s

Description: Hickory with dye

Size/Form: 5 1/8x 123/16x 6 11/16in (13 x 31 x 17 cm)

Collection: Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, YPM ANT.145107

As the very first entry in the catalogue for Places, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art, this painted Mohegan basket occupies a position of both literal and symbolic primacy in this groundbreaking exhibit at the Yale University Art Gallery–a primacy for which this basket is uniquely suited. The exhibit’s curatorial goals, as detailed by Katherine McCleary and Leah Shrestinian in their introductory essay, “Entangled Pasts, Collaborative Futures: Reimagining Indigenous North American Art at Yale,” notably include a desire to allow Indigenous people to tell their own story by centering Indigenous experiences of space and time in the exhibit’s presentation of native art, ideas which resonate deeply with the basket’s history and design as they connect to the exhibit’s primary themes.

Originally Mohegan and now held by Yale in the Peabody Museum’s anthropology collection, this basket exemplifies a dual sense of place, inseparable from Algonquian ancestral land just as it is from the violent processes of dispossession which enabled Anglo settlers to displace Algonquian-speaking people from the land on which Yale now sits. The basket’s primacy in the exhibit’s catalogue, as well as in the exhibit itself as a part of its first segment, “Places,” affirms the centrality of understanding Indigenous art on a localized level. McCleary and Shrestinian encourage local recognitions while acknowledging how the practice of salvage anthropology has worked to divorce Indigenous cultures from their land.

At the Peabody, this Mohegan basket has been part of a collection with a long history (McCleary and Shrestinian, 19) of participating in “the process of removing Indigenous objects and ancestors from their communities and lands,” thereby “help[ing] settlers legitimize their claims to Indigenous lands” (McCleary and Shrestinian, 21). In the Peabody’s anthropology section, it has been categorized as a natural history artifact, in keeping with an anthropological display strategy which “strips objects of their artistic merit” (McCleary and Shrestinian, 34) as well as of its deep and ongoing connection to its place of origin. But by showcasing the basket at the beginning of the catalogue in “Places,” curators McCleary and Shrestinian bring the basket’s Mohegan identity to the forefront, emphasizing the endurance of Indigenous artistry in the region. In this way, the Mohegan basket c. 1860 serves as an initial anchor to ground the rest of the exhibit in respect for its location on Algonquian land.

However, the Mohegan basket’s primacy does not only indicate a growing “commitment to regional Native Nations” (Blackhawk and Sutton, 41) around Yale, as described here by Ned Blackhawk and Summer Sutton regarding the prominent display of Iroquois Confederacy and Mohegan Nation flags at Yale’s Native American Cultural Center. The basket’s painted design, in addition to being deeply localized, has additional meanings which extend to the exhibit’s other themes: “Nations,” “Generations,” and “Beings;” it proves an integral starting point for the exhibit. In particular, the basket’s central motif, a large red dot encircled by smaller blue dots in a four-arced pattern, continues all around its circumference. According to the basket’s catalogue description and Mohegan Medicine Woman and Tribal Historian, Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel, the red dot represents the central life force of the universe, the blue dots symbolize the Mohegan people, and their four-arced pattern indicates the four directions. The blue dots and their arced arrangement bear a similarity to a prominent Mohegan design, the “Trail of Life” symbol, which consists of a curved line, representing the landscape, punctuated with blue dots, again representing the Mohegan people. In her preface to the exhibit’s catalogue “Belonging to the Trail,” Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel explains how the design expresses a sense of belonging with the landscape, and the belief that, as lives and generations process and fall away, a people can be led “back uphill” (Zobel, 12) through their interconnectedness to the natural world, the spirit world, and each other. This uniquely Indigenous perspective, which the basket references, is singularly apt at the beginning of Places, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art. As visitors begin their path through an exhibit unique in Yale’s history for its communal approach to Indigenous art by looking at this Mohegan basket, so may its designs serve as a reminder that Yale also embarks on its own journey: a trail which perhaps leads towards a “shared authority” (Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums, 1) of the University’s Indigenous holdings, one which hopefully will be governed by future dedication to empowering Indigenous interests, voices, art, and histories.

—Lauren Bond, Yale Class of 2021