Thomas Commuck’s “Indian Melodies” Brings Brothertown Indian Nation to Campus

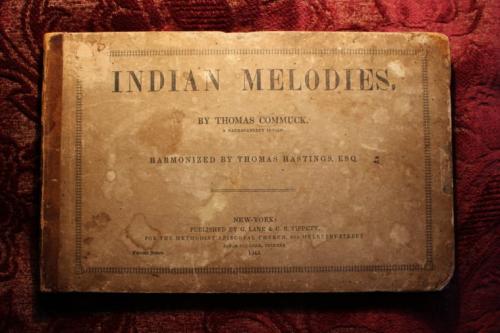

The centuries-old tradition of communal hymnal signing among Northeastern Native nations came to life in February. Gathered in Connecticut Hall (Yale’s oldest building), many members of the of Brothertown Indian Nation of Wisconsin came to Yale to participate in the performance of their ancestor’s, Thomas Commuck, “shape note” score. Recognized as the first musical publication by a Native American composer in Euro-American notation, “Indian Melodies” was published in 1845 after Commuck and his people’s migration to the Midwest. A copy is held in the Beinecke Library.

Through a collaboration between the Yale Indian Papers Project (YIPP), the Institute for Sacred Member (ISM), students within the Divinity School, performers across New England’s “shape note” musical community, and the Native American Cultural Center (NACC), Commuck’s “Indian Melodies” was performed for the first time in generations. Its verse, style, and rendering conjoin nineteenth-century Euro-American Christian musical practices with long-standing Northeastern Native cultural and musical expression.

Commuck’s music dates to a time when Native Americans, especially across the Native Northeast, incorporated Christian theology into their cultural and religious traditions. Such incorporation allowed Native communities to offset the deluge of Anglophone settler colonialism and to use recognized theological principles in either defense of their lands or in critiques of its taking. Commuck was Narrangansett, one of the Northeastern tribes that helped to form the Brothertown. Initially composed of tribal members from six northeastern tribes with shared linguistic, cultural, and regional backgrounds, in 1789, the Brothertown community settled on land provided by the Oneida in upstate New York. After white settlers began encroaching on Brothertown land, the tribe sent scouts west in search of land. The tribe then settled near the Menominee Indians, on the eastern shores of Lake Winnebago. After nearly 200 years of federal acknowledgment, the U.S. federal government unilaterally terminated that status in 1979. After spending three decades in a failed attempt at administrative re-recognition, the tribe is now seeking a congressional act to restore its nation-to-nation relationship with the United States.

Altogether, 88 singers from nine states (California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) and representing at least eight Native communities (Brothertown, Lumbee, Nehantic, Pequot, Schaghticoke, Ohkay Owingeh, Wirrarika, and Yaqui) gathered to sing Commuck’s shape note hymns.

As reported in the Yale News, Brothertown member Mark Baldwin relayed: “I had never been to New Haven before or visited Quinnipiac land. As a member of a non-recognized tribe [the Brothertown community is still fighting to achieve tribal recognition from the federal government] that has been dispossessed of its land, I understand the profound sense of loss Natives feel when they return to their ancestral home… As difficult as it may be to fathom, even though I had encountered Commuck’s work nearly 40 years ago, I had never heard it performed. I had heard Gabriel Kastelle’s violin version of ‘Old Indian Hymn,’ but never had I heard the tune sung by shape-note singers. The power of the raised voices, the words, and Commuck’s music combined to created a transcendent experience. While I stood in the square as ‘Old Indian Hymn’ was sung, I was bombarded by harmonies from all directions, making it easy to imagine what the congregation in the Methodist Church behind Commuck’s house would have sounded like in the 1850s. This singing is an integral part of the Brothertowns’ heritage, and nothing can compare to hearing it live.”

This collaboration took two years to materialize and started between Divinity School students and YIPP members, including YIPP Executive Director Paul Grant-Costa. YGSNA Member and NACC Director, Dr. Kelly Fayard, also joined in the collaboration. The extended Yale Native student, staff, and faculty community welcomed the Brothertown members at the Native American Cultural Center the night before their historic gathering.

See more at Yale News