Professor Brander Rasmussen Continues “Marvelously Detailed and Inventive” Inquiries into Native American Literary History

The presumption that the Native peoples of the Western Hemisphere lacked “civilization,” “history,” “art,” and other institutions of humanistic development has justified European colonization and Indigenous dispossession for centuries, and historians, anthropologists, and art historians have worked diligently for over two generations to expose the fallacy underlying such dismissive and at times racist presumptions.

Following the 2012 publication of Queequeg’s Coffin: Indigenous Literacies and Early American Literature (Duke), YGSNA faculty member Birgit Brander Rasmussen has continued her efforts to broaden the terms of Native American literary history and to recognize multiple forms of Indigenous literacy, writing, and ultimately “literature.” Current Native American and Indigenous Studies Association President Mark Rifkin described Queequeg’s Coffin as “marvelously detailed and inventive” in his 2013 lead review in American Literature, a study that also garnered Yale’s Heyman Prize for Outstanding Scholarly Publication as well as an honorable mention for the Romero Prize, one of two book prizes offered by the five-thousand member American Studies Association. In 2014, Professor Brander Rasmussen completed two anthology publications, a 5000-word overview on “Literacy and Language” for the Routledge Companion to Native American Literature as well as the first publication related to her newest research project on Plains Pictography and American Indian captivity narratives.

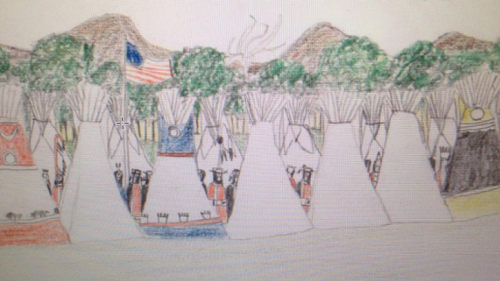

In “Toward a New Literary History of the West: Etahdleuh Doanmoe’s Captivity Narrative,” [in Contested Spaces of Early America (University of Pennsylvania, 2014)], Brander Rasmussen examines the narrative strategies underlying sets of captivity narratives of Kiowa prisoners of war held at Fort Marion, Florida. Often referred to as ledger books, or ledger art, Brander Rasmussen insists that such materials also constitute distinct and innovative forms of Native American literature. Assessing the continuities of Plains pictographic styles, conventions, and purposes, this chapter highlights the endurance of narrative forms of masculine achievement, cultural honor, and latent forms of anti-colonial resistance evident throughout Etahdleuh Doanmoe’s ledger portraits, dozens of which were commissioned by Fort Marion Captain Richard Henry Pratt, the eventual founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, one of the most infamous school in American history. In one such image of a Kiowa encampment in Oklahoma (see image), Doanmoe recreates the familiar cultural practices and sociality of his family and community, validating their distinctive communal forms at a time when Pratt and U.S. officials purposefully were attempting to eliminate such loyalties and practices.

Indeed, at Fort Marion, Pratt oversaw the “indefinite detention” of several dozen southern Plains prisoners of war, whom he fashioned into regimented units of military pupils. The martial instruction Pratt meted out to his captives in fact soon served as the basis for his assimilationist campaigns and pedagogy at Carlisle. For Native “students,” discipline, punishment, and loneliness characterized their years of incarceration. According to Brander Rasmussen, many, including Doanmoe, Howling Wolf, Bear’s Heart, and Making Medicine, rendered sketches of their childhoods, pervious accomplishments, as well as captivity to challenge the logics and discoursive terms of their captivity. Highly prized by art historians and collectors, such sketchbooks are increasingly becoming recognized by literary scholars and historians, and Doanmoe’s are held in Carlisle and at Yale’s Beinecke Library.

As detailed in Queequeg’s Coffin about Iroquoian wampum, Incan quipus, and Polynesian tattoos, among other forms of Indigenous literacy, Brander Rasmussen exposes narrative conventions, continuities, and adaptations found in Doanmoe’s ledger works, identifying southern Plains pictographic literary forms within his works. She has spent the Fall 2014 semester in residence at the Beinecke continuing her excavations into the corpus of Fort Marion Sketchbooks and intends to provide a broader assessment of the centrality of these “books” for the study of Native American literary history.